Sembene! - The tragedy of African cinema

The 2015 documentary, Sembene! is a welcome tribute to the father of African cinema, Ousmane Sembene. We spend a chunk of the film soaking in co-director (alongside Jason Silverman), Samba Gadjigo’s reverence for the Senegalese filmmaker as he recounts the impact of Sembene, decades before they eventually met. “When I was 14 I dreamed of being French, like the characters in the books I read in high school,” we hear Gadjigo say. Fast forward three years and the acuity of Sembene’s work had him proclaim “I no longer wanted to be French. I wanted to be African.”

The 2015 documentary, Sembene! is a welcome tribute to the father of African cinema, Ousmane Sembene. We spend a chunk of the film soaking in co-director (alongside Jason Silverman), Samba Gadjigo’s reverence for the Senegalese filmmaker as he recounts the impact of Sembene, decades before they eventually met. “When I was 14 I dreamed of being French, like the characters in the books I read in high school,” we hear Gadjigo say. Fast forward three years and the acuity of Sembene’s work had him proclaim “I no longer wanted to be French. I wanted to be African.”

Sembene, who died in 2007 aged 84, was a hero for boys like Gadjigo, who plays narrator here. He remains a hero to some of us now. The hero in any narrative normally comes out beaming on the backing and prayers of an audience. Looking back on Sembene’s life, we see that acclaim, that worship of his craft and rightfully so. But there are the heroes that reside firmly in a narrative wrapped in melancholy. "Show me a hero, and I will write you a tragedy,” I’ve heard said. Leave it to me to gravitate towards gripe material and a lingering sense of disappointment in a film that celebrates the legacy of a 40-year filmmaking career.

Africa appears to have trodden on his legacy – at least if the opening of the film is anything to go by. Gadjigo is visiting Sembene’s deserted villa, the “Calle Ceddo” on a Senegal seaside. It’s a heartbreaking mess. Reprehensible even. Filth, rust and dust decorate this villa and floor was littered with eroding reels of Sembene’s films when they should be encased in some museum in Dakar like the treasures they are. As our narrator put it: “His legacy is rotting”. Gadjigo talks about his mission to preserve Sembene's film work, his personal effects, his legacy and we clearly see why. There would have been tears in my eyes if I wasn’t surprised.

Thank God for this documentary which projected another dimension to the Father of African cinema and is an important step in that mission to preserve Sembene’s legacy. “Calle Ceddo” translates to “house of the free man” and that is pretty much what Sembene wanted for Africa. He strove for that mental liberation, first via prose till he realised most of Senegal (at the time) was couldn’t read nor write. So he turned to the magical art of cinema to provide a voice to and for the African, especially important in that period of early post-colonialism. He proved to quite the wizard, especially considering he was mostly self-taught.

Before diving into his work in cinema, some light is shed on his early life, like when he was expelled from his school from punching in the face his white teacher who had slapped him. Fate led him to the white man’s land, Marseilles, France, where he made a gruelling living unloading coffee sacks from ships and eventually broke his back. His physical incapacitation provided him with the opportunity to broaden the capacity of his mind with mostly Marxist ideals. He followed this up with his first novel, Black Docker, about an African dockworker who murders a white woman who tried to steal the manuscript of his novel and claim it as her own.

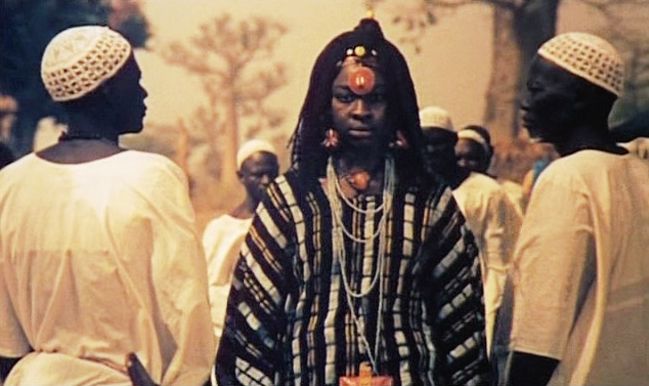

Black Docker carries that idea colonial exploitation that permeated his later creative endeavours, prime among them his resistance trilogy starting with Emitai in 1971, running through to Xala in 1975 and then Ceddo[/i] in 1977. Emitai narrows in on a Wolof village in colonised Senegal which rises up in protest against the mini-occupation of their village over rice. Of course, Emitai is more nuanced than this mini synopsis and the documentary recalls some inspired imagery, including that shot with the curious baby girl enamoured with a soldier and his rifle, who is then forced in a short retreat.

Sembene on the set of Emitai

For Xala, Sembene! takes us behind the camera and provides the kind of insight that makes the second viewing experience infinitely more enriching. It reminded me of illuminating awareness derived from Roger Ebert’s book on Martin Scorsese, which outlines the key influences New York director’s work. I never truly appreciated Mean Streets till I read Ebert’s book. Then I could not push Harvey Keitel’s hand hovering over a candle out of my head. On the surface, Xala derides the corruption and excesses of African governments and the African elite. But it also proves to be actually more subversive than first perceived. Sembene’s bold film actually has a key character directly modelled after Senegal’s president of the time, Leopold Senghor. Senegalese folk would know this, but I found this surprising, probably because contemporary Ghanaian cinema doesn’t even stumble into daydreams about being subversive.

I also got the sense there was an underlying sense of frustration and disappointment in Xala, a sentiment that was probably true of Sembene himself. Gadjigo’s narration conveys the hope, promise and excitement that came with African liberation. We are treated to joyous shots of our own Kwame Nkrumah, Sékou Touré of Guinée, Patrice Lumumba of Congo among others, at their glorious best. Most African nations were liberated from colonial rule circa 1960 and a new dawn beckoned. But history tells us decades of military dictatorships and the vampirism from the upper class awaited. In my short lifetime, the “Long Walk to Freedom” has morphed to Nelson Mandela’s granddaughter, Ndelika, turning her back on the ANC – a recent marker of the eroded promise that has plagued the continent.

The footage of a trodden Patrice Lumumba brought back the heartbreak from the first time I read about the Congolese leader. Lumumba was so young and full of promise and the obscene sight of soldiers treating him like street corner ruffian ready to be lynched still has me reaching for a vomit bucket. For Sembene’s home of Senegal, he might as well have been under French colonisation again, as far as his standing as creative was concerned. The Senegalese government had no interest in reflecting on the societal mirror his films presented and he was subjected to harsh censorship and scrutiny as typified by the reception of the final film in his resistance trilogy, Ceddo.

Ceddo narrowed in on religion, Islam, aligning it with the oppressive and shackling waves of whence. The attack on Islam ruffled more feathers than his previous works, so much so that Ceddo was never screened in Senegal till 1980 after President Senghor’s resignation. If history has taught us anything, it is that the prophet’s home is the wilderness as his own never accept him. Tellingly, Gadjigo described Ceddo[/i] as more of a critique on how the ruling powers use Islam as an opium for the masses. By the way, the government’s reason for banning Ceddo; it set a bad example for lay people with bad spelling. Senghor banned the film on the farcical pretext that the title misspelt Ceddo, which is supposed to be spelt “Cedo”. The farce is compounded by the fact Senghor is undoubtedly a pan-African literary icon but we know what politics does in this part of the world.

I haven’t seen Ceddo. I’m slowly making my way through Sembene’s back catalogue and Sembene! has its bit to say about his feature works, but Gadjigo’s film is ultimately Sembene 101. To the initiated, Sembene! will leave you wanting more. The few details it touches on speak to the degree of conscious thought put into the simplest of sequences. Consider the opening of , ever so subtle, that outlines how the African masses were ostensibly segregated from an independence that was as much theirs as the icons that led the liberation struggle and turned their back on them. It brings to mind the recent discussions we’ve had with regard to the marginalisation of chiefs, protesting veterans, market women and the like as far as Ghana’s independence story is concerned.

These details are a painful reminder of certain dysfunction at the foundational levels of a lot of our nations. Maybe we are graced with another documentary exploring the themes in Sembene’s work much more exhaustively and the more important question of their impact, or lack thereof. I saw Sembene! at an African Film Society screening and whilst Sembene’s work is showered with cinematic grace, wielding waves of historical insight for the largely middle-class gathering, I hardly think Sembene made his film’s for guys who wear Che Guevara motifs or marched for Cuba and Fidel Castro. That’s why Sembene didn’t release his films to video but instead went from village to village with a projector and generator so he could spread the consciousness to those in need. "Africa is my audience; the west and the rest are markets," Sembene has said. But another dysfunction, this time in Africa’s business of film, means the canker in our production process and distribution issues leave African audiences as markets for chaff from the west.

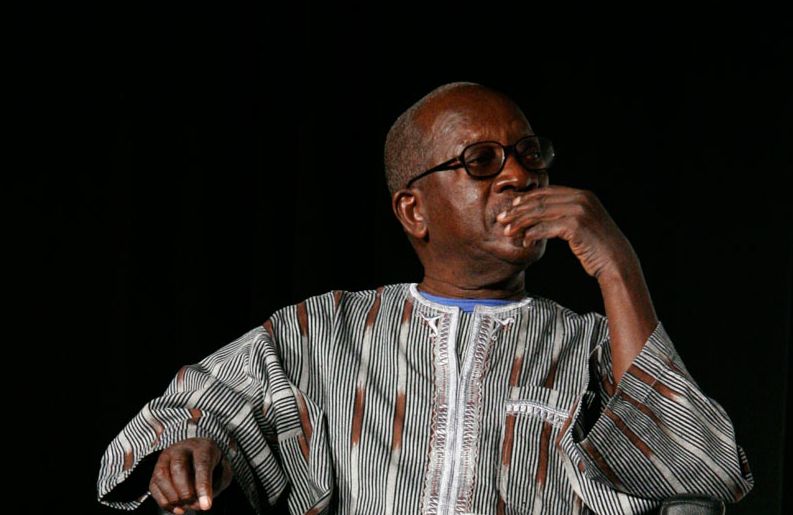

Sembene and Gadjigo

Sembene is heralded as the godfather of African cinema but Gadjigo stops short of calling him the messiah of African cinema. Every director, in truth, should walk in the mould of John the Baptist, laying stepping stones for future directors. Sembene certainly inspired filmmakers down the line and I bet some government’s wanted his head. But he also had a bit of an ego which pushed him to some disappointing lengths. Sembene had set up a fund for younger filmmakers but raided that fund at the expense of two younger directors to execute his 1988 film, Camp de Thiaroye, about the Thiaroye Massacre by French authorities of returning African soldiers from the Second World War – think Ghana’s Christianborg Shootings and ultimately a spiritual sequel to Emitai.

Of course, Sembene justified this. He said Camp de Thiaroye had to be made and Gadjigo’s documentary doesn’t sneer, it just shrugs – even at Sembene saying he would sleep with the devil to make a film. Gadjigo has his biases and places Sembene on such a high pedestal. Going back to the opening, he talks about how, for the first time, he wanted to be and was proud to African; all because of Sembene’s creative work. A certain chain of mental slavery was broken by the medium of cinema, the same chains that exist today. I’ve read my fair share of illuminating pan-African literature but there is some joy that comes with seeing a similar vision translate to the big screen whilst establishing a cinematic language conducive for African cinema.

This post is closer to obsequious rambling than a review. Or maybe its a bit of both. I feel like I have given up on Ghanaian cinema but that desire for vibrant African cinematic storytelling remains. Which is why I turned to classic Sub-Saharan Francophone cinema, and it turns out there’s a goldmine on YouTube; with work from intriguing directors like Djibril Diop Mambéty, Abderrahmane Sissakom, Souleymane Cissé and Idrissa Ouédraogo waiting to be explored. I don’t think the mainstream had much praise for Sembene and these other directors, except maybe for France. The few times I hear of them, someone is tweeting with enthusiasm ahead of a screening in an indie theatre in LA or Oregon. But thanks to folk like our African Film Society, some of us are afforded the opportunity to time travel to illuminating cinematic landscapes whilst we hope for a rebirth for our contemporary filmmakers and mother's happiness.

-

By: Delali Adogla-Bessa/delalibessa@yahoo.com/Ghana