Black Panther and Ryan Coogler's definition of Africa

The rambling below contains spoilers to Black Panther.

The rambling below contains spoilers to Black Panther.

Just how angry is Ryan Coogler, If he is at all?

That’s been one of the questions on my mind having seen ‘Black Panther’. Marvel gave Coogler the keys to the Black Panther vehicle and he took them to the promised land, delivering an incredibly personal film, opening up his soul to reveal a whirlwind of heartache, frustration and fury.

Sometimes, cutting to the core of a screenplay is as simple as musing on the opening and closing scenes, a la 'No Country for Old Men'. Much will be made of allure and wonder of the East African Imaginarium of Wakanda; beautifully imagined in its tactile splendor and arresting Afrofuturist visuals. But Coogler's first port of call is a basketball court in Oakland one 1992 evening. Some kids are balling, making do with a makeshift hoop fashioned out of a plastic carton. In an apartment overlooking the court, two men are planning what initially seems like a robbery or hit. We also notice news on the TV carrying footage of police bearing in on some black men. That’s the first hint of Coogler’s agenda.

It turns out the two men are from Wakanda. We become aware of this when, like an apparition straight from your average Nollywood film, their king, the Black Panther of that era, T’Chaka (Atandwa Kani) appears to them, with suspicions of treachery. The two Wakandans are spies in the US. More importantly, one of them is T’Chaka’s brother, N’Jobu (Sterling K. Brown).T'Chaka's suspicions are with basis. N'Jobu is caught with the stain of treason all over his hands. He has helped an outsider lay hands on Wakanda’s sacred vibranium, the most powerful substance on earth outside an infinity stone.

This early confrontation is only one side of the story. The other side of the story, revealed to us by flashback, much deeper into the film, paints a more layered picture of N'Jobu and his betrayal. His time as a spy in America has been marked by disillusionment and despair. The state-sponsored racism, wanton killing of black men and the assassination of black leaders have crushed his spirit, leaving him radicalised. Probably for the first time in his life, Wakanda, his homeland, did not matter. The revolution was more important – worth dying for.

In a stunning moment, the king’s brother does choose death. He whips out a gun but before he can even blink, T’Chaka’s claws are buried in his heart. It’s the original sin that gives Coogler’s story a rock-solid foundation, albeit one stained by blood from this act of fratricide.

Moments later, down below, on the court, all the kids stand in awe of the faint bluish glowing lights departing into the clouds, save for one, who runs up to find and cradle his father's dead body. It’s a moment that calls back beautifully to the death of aged T’Chaka (John Kani) in 'Captain America: Civil War', as his grief-stricken son, Chadwick Boseman’s T’Challa, holds his father’s dead body after a bomb blast at the UN. Pure poetry. The time spent in this Oakland neighbourhood is detailing the birth of the most flawed of heroes, in Coogler’s mind. What follows is the tragic journey of a death foretold, mirroring that of not only his father but of ancestors from centuries earlier.

Enter Michael B. Jordan’s Erik Killmonger, son of N’Jobu, joining the list of poignant black characters that have graced the world of cinema. Killmonger has widely been hailed as the finest Marvel villain and rightfully so. He is a nuanced portrait that provides somewhat of an answer to not only why Coogler may be angry, but what prompted such emotions. Killmonger's mission is simple, buoyed by the eternal spirit of resistance and executed with uncompromising malevolence: take over Wakanda and use its wealth and unmatched resources to empower disadvantaged blacks worldwide, in line with his father, N'Jobu's legacy.

Kilmonger’s drive is juxtaposed with Wakanda’s apprehension of the wider world and desire to maintain the appearance of just another poor African country. Both sides seemingly justified in their stance. The world has done nothing but take from Africa, striking down beacons of hope in the process. From Kwame Nkrumah and Patrice Lumumba, in the ‘60s to Muammar Gaddafi (who incidentally had an all-female elite guard) just at the onset of this decade, iconic, visionary leaders have fallen to sometimes barbaric tactics from the west. So, the "Keep Wakanda Great" philosophy will have some support from the people swirling in the vortex of post-colonial anxiety. As T’Challa notes, showing Wakanda’s hand would expose the country to hyenas like Ulysses Klaue (Andy Serkis), who had already struck gold. On the other hand, we have marginalized black people living in a world of blood and fire, the kind of hell we've seen represented in Katheryn Bigelow’s 'Detroit' or Dee Rees’ 'Mudbound'.

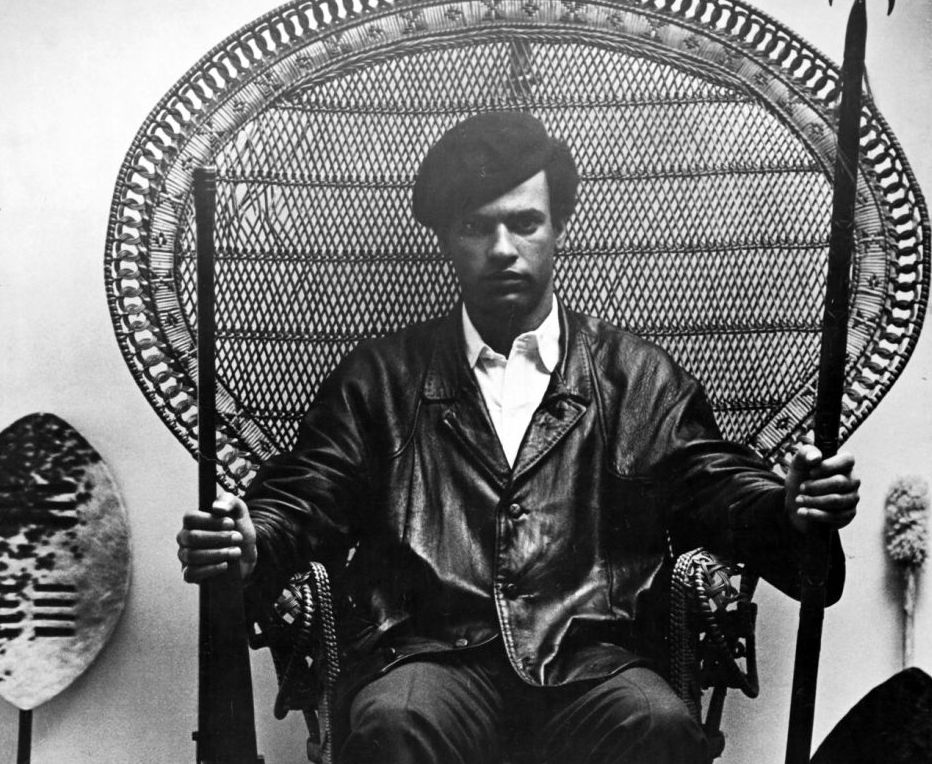

I take us back to Oakland, Coogler’s hometown and also the setting of his first film, 'Fruitvale Station', which recounts the last day in the life of Oscar Grant, who was shot and killed by police in a manner we have seen reported time and time again. The protests that shook American cities under the mantle of the Black Lives Matter movement after string of similar police killings may have simmered down but the eye is still on the ball for Coogler some five years after his directorial debut as streaks of rage still colour his handling of 'Black Panther' the film and the idea.Aside from wanting control of Wakanda, it is clear Killmonger really wants the mantle of Black Panther. I imagine he would have grown up in Oakland with the Black Panther embodying two constructs – a leader of an African nation “running around in a catsuit” and also the revolutionary socialist organisation formed in 1966 (four months after the Black Panther comic was conceived) by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale also in Oakland.

History has never been more important to the way a Marvel movie is contextualised. The reach of the past extends from Coogler’s back catalogue, where he pays tribute to Oscar Grant, an Oakland hero in his own right, to what the Black Panther symbolised long before I stumbled upon that Avengers animated movie which introduced me to the comic book version.'Black Panther', is a unification bout, trying to marry the idea of the Black Panther being the king of Wakanda with the radical roots of the Black Panther party Huey Newton conceived. The result is some measure of compromise after the meditation on the simplest of superhero ideas made popular in Sam Raimi’s Spiderman – power and responsibility.

The rage-filled Killmonger will not get his way. Like David in the Bible, Coogler seems to be telling us Killmonger is a man after his own heart. But there is too much blood on his hands to have him lead men into the promised land. He is a baddie, after all, reveling in the black hat he dons. He has been corrupted by hate and lacks the humanity required to be anything close to a good leader. There is, however, a truth Killmonger embodies, painfully buried by the nation of Wakanda. This truth, by force of will, remerges to reveal to T’Challa that there is a wound that needs healing and at the very end of 'Black Panther, T’Challa is setting up Wakandan outreach center in Oakland, at the same apartment complex in which N’Jobu and the young Killmonger once lived. We assume it will be the first of many. Penance and reconciliation.

Oh how I wish the dichotomy between T’Challa and Killmonger had provided more heft in the actual film. The idea of a broken T’Challa, angry at his father's miscarriage of justice and realising he will have to strike down, much like his father did, something noble, but misguided, is immensely distressing in its Shakespearean inflections. But like I noted in my review of 'Black Panther', the leash of the Marvel machine can only get so loose.

Taking time to really reflect on 'Black Panther', it is noteworthy that Coogler has stripped down the illusion or perfection that has characterised Wakanda. I’ve been scolded for comparing 'Black Panther' to 'The Dark Knight'. A DC head and Marvel troll, a friend of mine cried. Well here comes another DC drop, straight from 'The Dark Knight', which still reigns supreme. Coogler is the Joker, eager to reveal to us our primal selves and the innate corruption that goes with it. Wakanda is Harvey Dent, held up to be the bastion of equity and progress but with the flip of a coin, chaos ensues.

I don’t imagine Coogler to be a man who takes stuff for granted; just opting for random shots, and engineering throwaway lines. Everything should be taken as some extension of Chekov's gun. To cite an observation on Twitter, Wakanda is the nation with the greatest army in the world, a hi-tech wall around its borders and an ingrained aversion to refugees. Yikes.

To dwell on the fact this final third of 'Black Panther' has a group of plotters scheming with the CIA to overthrow Killmonger, who had become king in the masses will be a bit of a stretch. I wonder if some pan Africanists started palpitating when Everett Ross (Martin Freeman), a CIA operative, was literally shooting down airships sending caches to blacks in need, regardless of the fact these airships were about to spark a war.

The point is Wakanda is a mess, resembling the fractured African states that have scarred the continent and when the final act comes around and Wakanda is basically engrossed in a civil war we realise that the likes of Botswana are more deserving of the utopia status. It’s basically more of the same: lies, deceit and death.

But behind these dark clouds lies redemption and rebirth. Coogler redefines Wakanda as a beacon for pan-Africanism and Black Nationalism. He is reminding us of what it means to be African, drawing, directly or indirectly, the themes that defined the genesis of African filmmaking – resistance.

The grandfather of African Cinema, Ousmane Sembene, outlined the way but we have generally strayed from the path. Going back to the apartment in Oakland, where all truth is revealed to us in this film, we are invited to think on which of us have lost our African identity: the black Americans, generally perceived as woke as hell and angry at their government for brutalising them or the Africans droning through life like the Zombies Fela sang about.

Maybe if we were minorities in our own continent, we would fight more for each other. Maybe if it was a white man like devil incarnate W.P. Botha depriving us of good health care and education, stripping us of our deeds and dignity, we would stream onto the streets, like the youth of Soweto did, ready to risk it all because attaining true freedom meant something. But since it’s someone of the same from our own ethnic group or of the same skin colour, we sit in the burning house and just say: it’s fine.

That Coogler is angry isn’t in doubt. On a certain level, he is asking his audience, he is asking me if I am angry enough with him. He does so the most subtle but incisive ways. Like Mookie starting a mini-riot in 'Do the Right Thing' to get our attention, an insidious character like Killmonger, who has lied and killed to sear his way into our hearts, becomes necessary for 'Black Panther' to resonate. If you aren’t angry then you are lost, he tells us. Thankfully we aren't completely lost. The spirit of resistance, though not a strong as it could be, still burns. The Women of Liberia movement which trooped from Monrovia to Accra in 2003 during the country's civil war reminds us of that. The thousands that hit the streets every week in Lome to rally against a dictator should give some of us some cause for reflection.

Africa, in Coogler’s mind, transcends the mere continent that was diced up and shared like pork strips at a barbeque. It’s a spirit, a shared history, making an apartment in Oakland just as important as the old Polo Grounds in Accra or a small 8x7 foot cell on Robben Island prison. His true African utopia.

-